Coin Flips and Gödel, Escher, Bach

I invite you to a simple statistical experiment where we flip some coins, and do basic analysis of what happens. It is not going to be complex at all, relax and enjoy.

The Experiment

Suppose you have a coin. It is minted by the government. You have no reason to believe it has been tempered with such that it come heads more than tails. That is to say, you are pretty sure it is “fair”.

You could test if the coin is fair by tossing it yourself, say, 100 times. It will take time, and you might still not be as convinced of the fairness as you would like to be. What do we do, then? We simulate coin tosses on a computer!

To simulate the coin toss process on a computer, we will mark Heads as 1 and Tails as 0. I am going to use Mathematica to simulate, it should be fairly simple to follow what we are doing.

In[]:= RandomVariate[BernoulliDistribution[1/2], 100]

Out[]:= {0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1,...}

Here we are using BernoulliDistribution function (see Wikipedia), which is a function that can simulate coin flips. Since we are saying that the coin is fair, we are saying that the probability of coming 1 or 0 is 50-50, i.e. 1/2.

The catch, I confess, is that by simulating the flips on computer we are specifying the probability instead of figuring it out. But let’s stick with it for this simple situation.

Now that we have a list of 100 simulated coin flip results, we need to calculate the proportions of Heads and Tails. By calculating the proportion of Heads, we will be able to tell if the coin is actually fair or not (again, in the case of this simulation, we know it to be fair). If the Heads come about 50 times, we can safely say the coin is fair. In terms of proportions, that would be a split of 0.5 Heads and 0.5 Tails. In other words, approximately 50% Heads and 50% Tails.

How shall we do this? Well, we can sum the 1s in our list of coin flips. Recall that we just created a list of results in the code above. This will tell us the total number of heads. Simply divide the number of heads by 100 (the total number of flips) and we know the proportion of Heads! You can extrapolate to find the proportion of Tails as well.

In[]:= tosses = RandomVariate[BernoulliDistribution[1/2], 100];

In[]:= N[Total[tosses] / 100]

Out[]:= 0.456

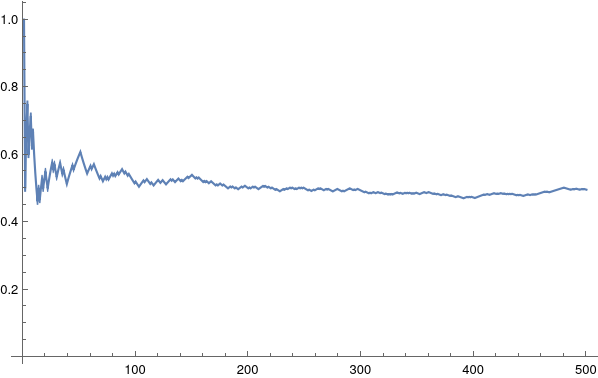

Fairly close to 0.5! We could simulate various types of coins and sample more data by flipping even more. Below is what the proportion might look like for 500 flips of a fair coin. The graph shows the updating proportion of heads, as we keep flipping the coin.

I’ll take the opportunity to show-off my Mathematica kung-fu skills. This is how the graph was generated:

tosses= RandomVariate[BernoulliDistribution[0.5], 500];

ListLinePlot[

MapIndexed[Total[tosses[[;; First@#2]]]/First@#2 &,

tosses], PlotRange -> All]

Breaking out of the system

Now I would like to point out an interesting jump our brains made in this process.

When we started, we thought of using 1s and 0s to represent Heads and Tails for computational convenience. Then we started summing the 1s to calculate total number of heads! Had we chosen some other representation such as string “H” as Heads and string “T” as Tails, we would not have been able to simply sum (which is Total in our code). But somehow we noticed that exploiting our representation scheme will aid us in doing what we are aiming for.

The Heads and Tails have nothing to do with 1s and 0s of course. If we were to do things mentally, we could do a “tally” of heads and tails. The “lower level” Head and Tail of the coin itself has no such features. However, the representation we chose allowed us to make a connection between coin flips and the algebraic property of sums such that we could “hack” or “shortcut” our way to answer by stepping outside the system of coin-flips and stepping into the algebraic system.

This is called an Isomorphism. We found a sort of translation between two systems (however limited) and managed to oscillate between the two for our convenience. This ability of forming isomorphism, GEB suggests, is hinting towards what intelligent systems might be doing: sufficiently complex systems manage to start forming such isomorphism between meaningless symbols and acquire meaning.

I hope you - a sufficiently complex system - managed to introspect on your own ability to form isomorphism.